Ann Marie Ackermann, author of Death of an Assassin: The True Story of the German Murderer Who Died Defending Robert E. Lee, will be at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, on April 9. She will give a book talk with the Tippecanoe Civil War Roundtable. This is her third trip from Germany to the U.S. to promote her book since it was released by Kent State University Press in September 2017. This September, the German edition will be released by Silberburg Verlag. Ann Marie Ackermann agreed to write a guest post on the method she used to adhere to copyright laws in the U.S., and for the new edition, in Germany. Welcome Ann Marie Ackermann.

Ann Marie Ackermann, author of Death of an Assassin: The True Story of the German Murderer Who Died Defending Robert E. Lee, will be at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, on April 9. She will give a book talk with the Tippecanoe Civil War Roundtable. This is her third trip from Germany to the U.S. to promote her book since it was released by Kent State University Press in September 2017. This September, the German edition will be released by Silberburg Verlag. Ann Marie Ackermann agreed to write a guest post on the method she used to adhere to copyright laws in the U.S., and for the new edition, in Germany. Welcome Ann Marie Ackermann.

You can’t control where lightning will strike. Your best protection is a lightning rod, so that when it does strike, the shock will be deflected.

You can’t control where lightning will strike. Your best protection is a lightning rod, so that when it does strike, the shock will be deflected.

Copyright law is no different.

You can’t control whether someone sues you, but advance preparation can help keep liability from sticking. Physicians ask for informed consent agreements, family lawyers ask for prenuptial agreements, and insurance contracts restrict the type and amount of damages. Each example is nothing more than a liability lightening rod.

As an author, you need a lightning rod too. If you plan to reproduce images or quote other authors, you need to secure written permission unless the material is in the public domain. Good records of your permissions will help you and your publisher in the long run. Not only will it speed up the book’s journey to print, it will also protect you in the worst case scenario.

Organizing your permissions

I must have done something right: My publisher said I’d done a better job organizing my permissions than most authors. My system made it easier for me to document my permissions. Here are my tips:

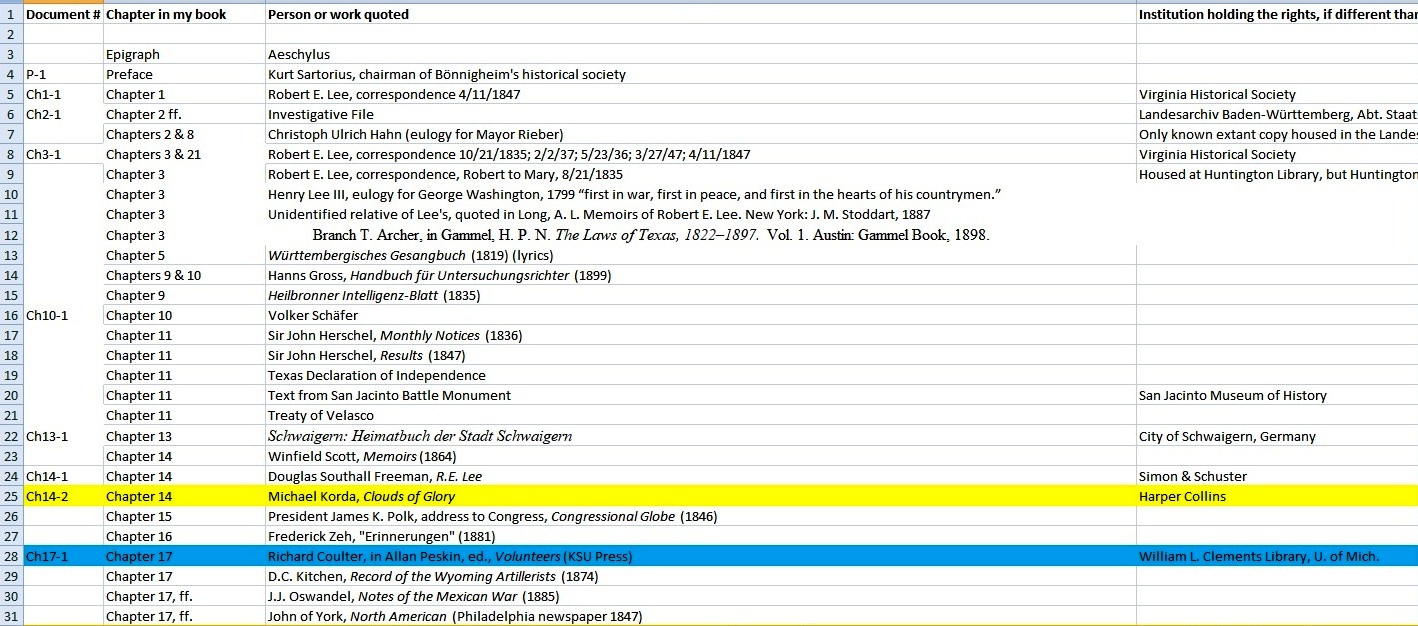

- Set up two spread sheets, one for textual permissions and one for illustration permissions. As you write your book, set up a line for each item that needs permission and add information to your spread sheet as you receive it.

- Set up the following vertical columns:

- Document number. Numbering each item that requires permission will help you organize your permissions and locate documents in your files. I numbered my documents according to chapter. If there was more than one quote or illustration in a chapter, I numbered those, too, e.g. Ch. 1-1, Ch. 1-2. That makes it easy to locate the passage or image in the book. I wrote those numbers on the hard copies of the permissions I sent the publisher.

- Location in the book. Include a page number or at least a chapter.

- Person or work quoted, or source of an image.

- Institution holding the rights, if different from the author. Here I entered the publisher, archive, or library that held the rights.

- Public domain? Here I entered a check if the item was in the public domain and mentioned the reason why, e.g., published before 1923, or government document. For one of my items, I even referenced a legal opinion from a lawyer. Providing the reason helps the publisher confirm the public domain status.

- Fair use? Here I entered a check if a text quoted could be considered fair use. It’s better, however, not to do any guesswork here. Just to be certain, I obtained written confirmation from the publisher of that text that it considered my quote short enough to be fair use.

- Document granting permission. Enter the type of document, e.g. letter, e-mail, or a statement on a library’s website, along with the author and date.

- Conditions of permission. Some institutions will grant permission provided you pay a fee, provide a complimentary copy of the book, credit the item in a certain way, or any combination of the above. I enter the conditions here, so it’s easy for me and the publisher to check whether the conditions have been met.

- Contact person. The name of the person providing permission and his or her institution.

- Contact information. Enter the e-mail address or mailing address of your contact person here so your publisher can contact him or her if necessary.

- Permission for amount in print run. Some permissions require you report the the number of copies to be manufactured by the publisher. It’s important to know the size of your publisher’s intended print run and obtain specific permission for that amount. If you don’t know, then ask your agent or publisher for this information to complete the copyright permission request. In this column, I enter the highest number for which I’ve received permission. In case your book goes into a second print or a translation, this column will tell you in a glance which permissions you need to renew.

- Permission for the type of publication: Some institutions specify whether the permission is for hardback, paperback, electronic versions, or for which language. Make sure the permission you receive covers those bases and check off this column.

- Worldwide rights? Unless your publisher is planning to sell your book only in one country, it will need a permission that allows it to sell the book worldwide.

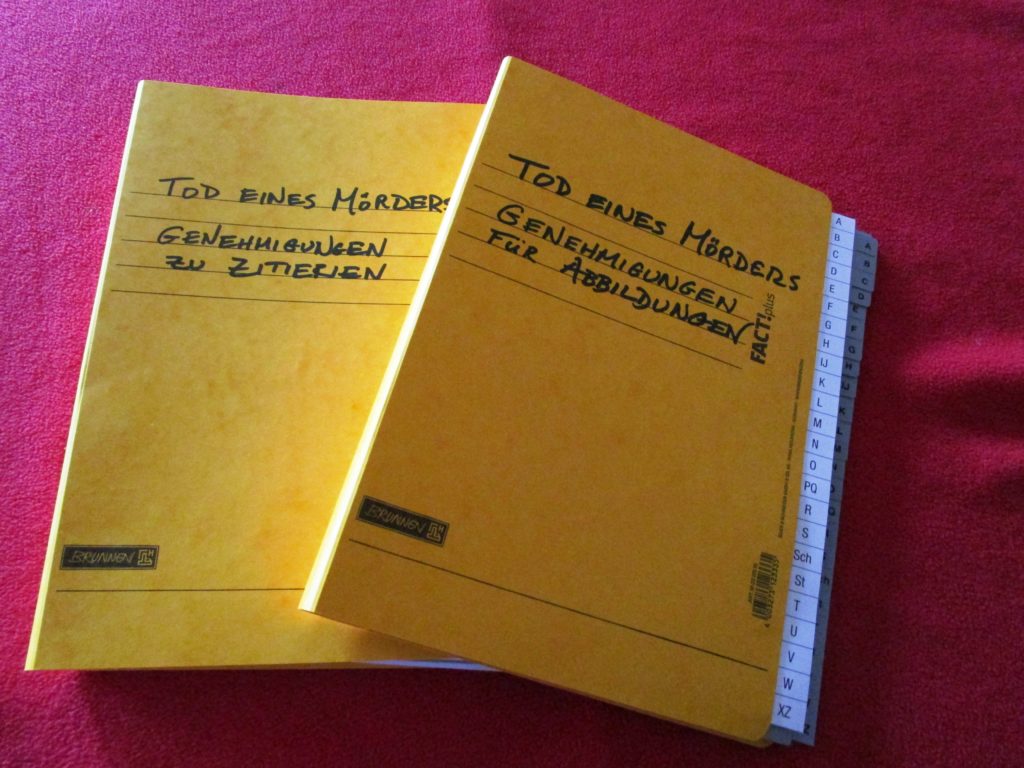

- As your permission documents roll in, print them out, number them according to the document number in your first column, and organize them in a notebook or folder by chapter. I created one folder for textual permissions and one for illustration permissions.

- Send the folders to the publisher along with the spread sheets. The spread sheets should help you and your publisher find any document you need in a jiffy.

With the last step, you’ve constructed a functioning lightning rod for you and your publisher. In case someone does complain later about a copyright violation, it will be easy to find the documentation that supports your permission.

With the last step, you’ve constructed a functioning lightning rod for you and your publisher. In case someone does complain later about a copyright violation, it will be easy to find the documentation that supports your permission.

Extra permissions for a translation

Extra permissions for a translation

When my book went into translation, I went back to my original spread sheets. The columns let me know at a glance whether a specific permission covered the German translation or whether I’d need a new one. For the new ones, I added some columns the foreign publisher might need. These included:

- Permission for the German language. If the original document granting permission did not specify that the permission applied to all languages, I needed to write back and obtain permission for the German edition.

- Print run. You’ll need to check whether your original permission allows a new print run of the size your foreign publisher is planning.

Don’t forget that different countries have different laws when it comes to copyright. Germany, for instance, does not recognize fair use. Its concept of public domain is different – older documents belong to no one, not the public. Your foreign publisher probably has a much better handle on its country’s copyright laws than you do. The best thing you can do is document why an image or quote meets certain copyright exceptions under U.S. law. That will enable your publisher to evaluate those grounds from its own legal system.

Don’t forget that different countries have different laws when it comes to copyright. Germany, for instance, does not recognize fair use. Its concept of public domain is different – older documents belong to no one, not the public. Your foreign publisher probably has a much better handle on its country’s copyright laws than you do. The best thing you can do is document why an image or quote meets certain copyright exceptions under U.S. law. That will enable your publisher to evaluate those grounds from its own legal system.

If you obtain your permissions and compile this information while you’re writing your book, you should be able to turn in your permissions at the same time as the manuscript. Your publisher will appreciate the chance to review them as early as possible. If you need to obtain a new permission, the sooner you get it, the better.

All that will help keep your book on its publishing schedule and protect it from a lightning strike. Good luck!

This is very helpful. I have some photos that I’m planning to use in my book-in-progress. Some I got from a county historical society. The director there told me I could use them privately, but to revisit her when the time came that I was closer to publishing.